A History of the Transient Realm

Table of Contents

- A Note on Historiography

- The Establishment of the Cycle of Ages

- The Previous Age

- The Start of the Transient Age

- Darkness Arrives

- The Founding of Alchascelge

- The Founding of Eftascelge

- The Founding of Massascelge

- The Years to Follow

- The Centuries' War

- A New Magic

- The Founding of Sirin's Firth

- The Fall of Sirin's Firth

- The Campaign on Dragascelge

- The Battle at Cravagoule

- Establishing a New Order

A Note on Historiography

The vast majority of this history was written by Bird Beetle, the Goblin of Sugarcane Hollow. Having traveled the Realm and conversed with all manner of travelers and gods, B.B. made use of his impeccable memory to record all he had learned of the Globe's history here. While this document attempts to be as accurate as possible in its description of the order and nature of these events, notes taken as fact are occasionally affected by B.B.'s personal biases and perspectives (generally harmless as he is). To address this, notes by myself have been added in red, though I have access to information and perspectives that B.B. does not, so these notes may not be in line with what is believed to be fact by the majority of those within the Transient Realm. -F.F.

The Establishment of the Cycle of Ages

There exist an infinite number of Realms. Each Realm, a plane of existence wholly separate from the others, is similarly infinite in size. The vast majority of these Realms (nearly all, it would seem) are inhabited by those Great Beings of Chaos, things absent of coherent form and infinite in size, whose presence defies Meaning and Order, without which Life can not form or prosper. In these Innumerable Realms of Chaos, there is no reason, no time, no shape, no consistency, no light, no dark, so potent the effect of these Beings' influence.

Order came with the Dawn of the Globe. The origins of the Globe are wholly a mystery, as there was no one living to witness it and so anomalous is its existence. The Globe is a seemingly unique structure as it exists in not one Realm, as most things do, but five simultaneously. Perhaps this superposition allowed for some degree of Order to form within the Realms the Globe occupied, an Order inherent in uniformity or similarity, enough at least to ward off the closest Beings of Chaos.

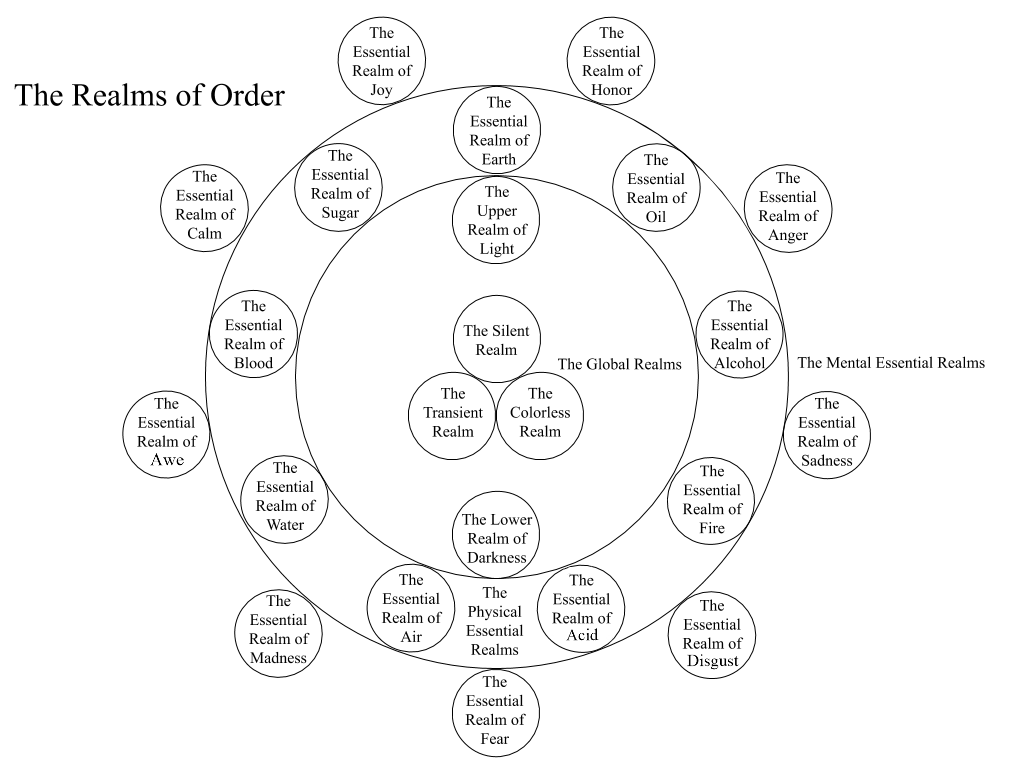

A reflection of this Order is seen in the orientation of the Global Realms which developed thereafter, as each Realm which held the Globe became distinct from each other in nature while still simultaneously holding the same Globe. The highest oriented became the Upper Realm of Light, contrasted by the Lower Realm of Darkness, and situated between were the three Neutral Realms; the Silent Realm, the Colorless Realm, and the Transient Realm.

The exact nature of the Globe, or the answer to the question of what the Globe actually is, is uncertain. There are a number of similar celestial spheres which have found themselves, one way or another, in the same Realms which the Globe occupies, likely originating from other Realms and only finding themselves within the Global Realms after somehow escaping the Innumerable Realms of Chaos. These are the Moons of the Globe, of which three rest in its orbit in the Upper Realm of Light (one blue, one rose, and one gold), one in the Lower Realm of Darkness (red as blood), two in the Colorless Realm (one black and one white), and one in the Transient Realm (a pale white). Still, compared to the Globe these smaller Moons are either dormant, infantile, or deceased, having not the power to exist in more than a single Realm or to generate any significant amount of Order. That is not to say that they are without influence, but that it is neither direct or dominant.

From this foundation of Order came the establishment of several important concepts. The first, and perhaps most notable, is the start of the Cycle of Ages. While the initial Age in the Cycle may have started differently from those that followed, the general pattern is as follows: To each of the Neutral Realms, a role is assigned, one serving as the Realm of the Living, one serving as the Realm of the Dead, and the third serving the role of the Vacant Realm. These roles are not determined at random, but rather in a set pattern that cycles as each previous Age ends: the previous Realm of the Dead becomes the current Realm of the Living, the previous Realm of the Living becomes the current Vacant Realm, and the previous Vacant Realm becomes the current Realm of the Dead.

Each new Age starts with the coalescence of a Being of Light in the current Realm of the Living, formed into a single being from the Souls of every deceased Living Being from the previous Age. The Being of Light is a consciousness with two goals: to preserve and expand upon the Globe's Order and to create and protect Life in the current Realm of the Living. The latter is achieved by creating Souls from Light and the Mental Essences (which are described later) and Bodies to house and replicate them formed from the Physical Essences (which are similarly described later). Once Life is created, the Being of Light is pulled through the Sun to the Realm of Light (the Sun itself being a large Line, or passage between Realms, to the Realm of Light from the current Realm of the Living).

Life thrives at the start of the new Age, with a new Realm to expand upon and guidance from the Being of Light to give its expansion direction. However, eventually Lines to the Lower Realm of Darkness will begin to open, and soon Beings of Darkness will enter the Realm of the Living, their goals being counter to that of the Being of Light: the destruction of Life. The conflict between Life and Darkness is what defines the length of each Age in the Cycle, as when the last of the Living dies, its Soul being transported to the Realm of the Dead, the current Age ends and the next Age begins anew.

The second concept afforded by the Order generated by the Globe is the establishment of the Essential Realms. Extending its influence beyond merely the Realms which it occupies, the Globe also affects many nearby Realms, dispelling the Beings of Chaos which occupy them and transforming the eighteen nearest into the Essential Realms. Each of these Essential Realms is an infinite expanse assigned one Essence with which they are wholly filled. Each Essence is a fundamental substance from which all things on the Globe are constructed, of which there are eighteen in total. Nine are the Physical Essences (being those commonly described materials of Earth, Water, Fire, and Air, in addition to the "Organic" Physical Essentials, which are Blood, Oil, Alcohol, Acid, and Sugar), which constitute the physical nature of things on the Globe, and nine are the Mental Essences (which are Joy, Awe, Honour, Calm, Sadness, Anger, Fear, Disgust, and Madness), which compose the mental, emotional, and spiritual nature of things on the Globe. As such, the Essential Realm of Water is an infinite expanse filled with Water, like some infinitely vast sea, and the Essential Realm of Sadness is an infinite expanse containing an infinite amount of the purest distilled feeling of Sadness.

As an aside, a common point of confusion concerning these Essences is the distinction between light, the fluorescence produced by Fire, and Light, the Essence defining the Upper Realm of Light and the Being of Light. While both make visible that which is obscured by Darkness, only Light originating from the Upper Realm is substantially opposed to Darkness. A Beast originating from the Realm of Darkness may fear the light of a lit torch due to its resemblance to that of the Sun, but would not be harmed by it as it would be in the presence of Light; the appearance of light produced by Fire does not equate to the conceptual and spiritual potency of Light.

These Essences, originating in the Essential Realms, find themselves in the Global Realms (that is, Realms which the Globe physically occupies) via Lines, dimensional pathways and connections between different Realms. Many are naturally occurring, almost instinctively, as the Globe has covered itself in a thick layer of Earth and Water and Oil and Air, which form the Mountains and Oceans and Skies on which the Being of Light may place their constructed Life (pulling the Essences from which Life is constructed through Lines the Being of Light would have opened themself).

The third concept afforded by the influence of the Globe's Order are the two Global Laws, the Law of Resonance and the broader Law of Coherence.

The Law of Resonance asserts: The Globe will work to reflect the Soul, the Body will work to reflect the Globe. This law is the basis of Line Magics and Essential Affinities, but finds itself manifesting everywhere. After all, as the Soul is held by the Body, this Law is cyclical: the Body and the Globe are in a loop of imposing their presences upon each other. The Globe molds the Body, the Soul directs the Globe, and the Body affects the Soul. A Soul may resonate with Fire, and for that Soul the Globe will make Fire appear. The Globe may demand the Body grow resilient, and the Body's skin will toughen. In a more indirect application, the Soul may associate an Image or Symbol or Phrase with Air, and the Globe will react as though that Image had the potential to produce Air. A Soul may resonate with another Soul, and the Globe will allow the Soul with stronger resonant potential to have influence over the other. It is the simplicity of this Law that grants it diversity in presence.

The Law of Coherence asserts: The Globe maintains a set of rules which replicate Order and dissuade Chaos. This is often broken into the Laws of Chronology (that time is linear, and events happen in an order), Consistency (that the makeup of a thing can not change at the Essential level; that the changes in a thing's composition are a result of the introduction of new Essences or the removal of existing Essences, as the Essences themselves do not change), and Contingency (that events happen because of other events, and nothing happens for no reason). It is through these that concepts of Gravity, conservation of Mass and Energy, and so on are maintained.

It is within the maintenance of these Laws and the preservation of Order that the Being of Light operates. This is represented best by the conflict of Light and Dark, Life and Beasts, or Good and Evil, where the Life created by the Being of Light is in conflict with the Evil Beasts produced within the Realm of Darkness.

Evil, the trait that characterizes the Lower Realm of Darkness, is conceptualized by two factors: the destruction of Life and the obstruction of Agency. Agency is the feature that most aptly characterizes Life, the ability of a thing to exercise free will or conceptualize its own initiatives and motivations, and so it is the most revered aspect of Life.

Evil is not to be confused with Chaos. Entropy is a neutral force, as it is represented by both Stagnation and Chaos. These concepts do not inherently negate or destroy Life or Agency, as Evil does. However, both are a threat to the Law of Coherence, and to Order as a whole; Order is disrupted when those with Agency are without direction, as the Stagnation or Chaos that would result in a lack of conflict would disrupt the Law of Contingency. The absence of the fight between Light and Dark would be a replication of Entropy, as there is no inherent Order in the absence of conflict. This would result, ultimately, in the destruction and deconstruction of all Meaning.

Note, here, two assumptions made of the nature of Meaning: that it is necessary for Life to continue happily and that it relies on conflict to be upheld. Perhaps Light wishes to propagate its own necessity, or it misunderstands the nature of Life in Chaos. After all, there is a paradox at the center of this process, that Light relies on the continuation of Order and Life, yet Life (the force which constitutes the Being of Light at each Age) is characterized by Agency, which is inherently a Chaotic trait. An inability to conceptualize a world that lives on without a Meaning ascribed to it is what drives the Being of Light to continue its propagation of Order. Additionally, an inability to conceptualize Meaning in the absence of conflict is what leads to the Being of Light opposing Darkness but simultaneously believing it could never fully remove its influence on the Globe, lest it leave the world Meaningless.

The Previous Age

After a myriad of Ages had passed since the Dawn of the Globe, a Colorless Age began. It is known that each of the Neutral Realms involved in the Cycle of Ages lacks something which the other two have: the Silent Realm lacks Sound and Voice, the Transient Realm lacks a Freedom of Form, and the Colorless Realm lacks, as its name suggests, Color. For this reason, the Life created in this Age was devoid of Color, its denizens adorned in Blacks and Whites, yet granted Voice and Shapelessness. In a rare occurrence in the Cycle of Ages, these particular denizens, having mastered the study of Shades, had created a wholly unified Kingdom with power so fully assured to its Rulers and their Enforcers that the forces of Darkness had all but entirely waned in their presence.

At the height of its power, this Kingdom was ruled by the Venerable Achromatic King Anhiwne and the Benevolent Diatonic Queen Gehiwaine. Their love and capabilities were apparent in their contrast, Anhiwne an embodiment of the Blacks and Whites of a model Ruler and Gehiwaine all the lovely Greys that spanned the difference. From this union came the birth of their first child and heir, Linhiwne, beloved by both and loving both in turn, a polite and regal child with a passion for seeing the many fluctuating lands of the Kingdom, from shifting shore to winding peak, and a passion for helping others, trusting the help to be returned when they ascended to the throne to continue the Dynasty.

This pleasant period did not last. On a cold morning, Gehiwaine passed away, not from the forces of Darkness or the actions of another, but from illness, her life cut short. Anhiwne, in his grief, turned his efforts from the protection of his Kingdom to the protection of his Kin. He sponsored the creation of a Palace designed by those Architects most well versed in the study of Shades and Forms such that nothing could enter and nothing could leave, should it protect his child from any harm similar to that which befell his late wife. Of course, their construction was flawless, and Linhiwne was moved to the safety of an inescapable castle.

Needless to say, this change did not have a positive effect on Linhiwne. Once well mannered and pleasant, they became angry and bitter, betrayed by their father who took the world from them in fear and disillusioned by a Kingdom in such glorious days that it could not reason the existence of death in a beautiful world. Of course the Architects would build a prison for an heir, should they believe that the decision not to would be the same as killing the child themselves; the heir was the future of the Dynasty, and it was too good a Dynasty to lose.

The resentment which grew in Linhewne was what invited a solution to their predicament into the Palace, not from the world outside but from the world beneath, as a Herald from the Lower Realm had found itself in the Palace Garden, having passed through a Line to the Colorless Realm formed from Linhiwne's anger. The Herald offered the heir a chance of escape, telling them that in the center of the Garden was a tree which would soon bear a fruit containing the essence which would allow passage from this prison.

Linhewne had known that those forces of Darkness that existed in the days before their parents' rule would offer such gifts in bad faith, but was so desperate to escape that they followed the Herald's instructions anyways, and had found the fruit which grew in the Palace Garden, a pure white pear. Biting into the fruit revealed the secret it held: red flesh, natural color, that which lay beyond the Shades, that which was antithetical to the Colorless Realm and would, with its very presence, destroy it. Color spread throughout the Palace Garden, washing the plants in Greens and spilling out of the Palace in shades of Blues and Reds, any Denizens of the Realm witnessing it perishing at the sight.

Anhiwne, having seen the bright colors of sunset spilling from his Palace, suspected the worst and was quick to enter the Palace himself, breaching the impenetrable walls that he had erected by force of will alone and finding, at its center, a fruit with a single bite taken from it on the ground and Linhiwne nowhere in sight. In suit, Anhiwne raised the pear to his own lips, and as the Age ended with a bright blue sky, he, too, vanished from the Realm.

The Start of the Transient Age

As it began, a Being of Light coalesced in the Transient Realm. Bounded by Form, as is inherent in the Transient Age, the Light took the visage of the First Goddess, later named Utforalguten Patil.

Tasked with creating Life before Darkness encroached upon the Realm, Patil set to creating plants, the simplest of her creations. Plants lacked mobility, and had Bodies incapable of single handedly holding a Soul, so primitive was their design. However, their design held its own advantages as well. Instead of having a single Soul rest in every individual plant, be it a blade of grass or an oak, many plants in close proximity would share a Soul, much larger than any individual Body could hold, which would serve as the Soul, Mind, and Will of the forest, field, or glade it represented. Additionally, the absence of a Soul in any individual Body allowed them to absorb and hold Light as they were exposed to it, something a regular Body can not do, as the strain of holding such a powerful Essence is usually too much for a Soul to bear without fraying or breaking. Still, against Darkness this Life would be ill suited in battle.

This Life did flourish more where the Globe's natural Lines were more abundant, and as it should happen there was a great abundance of them in the central region of the Globe, which did form a continual stream of many intertwined Lines known as the Great Line that roughly spanned the Globe's equator, an ever present band of Essential potential around which a great forest grew across the Globe's largest continent, separating the plains to the North from the hills and mountains to the South. In time, this forest would be named Beoralheome, or "The Sun-Painted Forest."

The second form of Life made by Patil were the animals of the earth, air, and sea, each with a Body holding its own soul and legs and wings and fins to travel the Globe freely. Perhaps the most diverse of Patil's creations, they took forms which best reflected their environments, in a natural correspondence with the Law of Resonance; the Body will work to reflect the Globe. In this sense, animals were perhaps the least directly designed by Patil.

It was with this Form of Life that the first major instances of predation occurred, where in order to acquire sustenance without the direct absorption of Light, they would eat other Life, the grazing animals feeding upon the plants and the hunting animals feeding upon the grazing animals. This, however, skirted the definition of Evil and did not directly invite Darkness; predation for the purpose of sustenance is not the destruction of Life as much as it is a form of preservation. As long as a balance is maintained, without this predation becoming excessive and thus harmful to Life as a whole, this was a natural process, and neutral in terms of morality. After all, the deer does not eat away at the field overabundantly, and the wolf does not eat the deer with malice. However, should Life eat harmfully, excessively, or with the motive to cause suffering, it would invite Darkness into the Transient Realm.

From the forms of these many animals, Patil drew the favorite of her creations. Unifying the horns of the grazing beasts with the teeth of the hunters, the scales of those in the sea with the fur of those on land and the wings of those which inhabit the sky, Patil crafted dragons, the largest and strongest of her creations. Each was gifted a Line to a Physical Essential Realm that rested within their chest from creation, fully internalized and attuned to their breathing, allowing them to exhale the Essence contained within with some great amount of force. They were also incredibly long lived, not dying of natural causes or even starvation (and rarely of unnatural causes, as their scales and horns were nigh impenetrable), and would have been a formidable opponent to the arrival of Darkness had it not been for one crucial fact; they could not reproduce, either a result of the composite form they were given, the amount of energy required to develop when a creature is so large and complex, the presence of an Internalized Line, or a simple mistake in their creation on the part of Patil. Indeed, they were impregnable yet not impregnatable.

Each dragon, on their creation, was also gifted a tongue, which, like Patil's own, could speak the True Names of every thing, the names which resonated most fully with the object it addressed. This tongue, however, quickly fractured, first into accents and dialects affected even by the specific articulation capabilities of a dragon's literal tongue within its own snout, and then into conceptual splinters, as one thing could have many names that resonate with it and a True Name that only really remained if it was upheld and understood. Of these many fractured tongues, only that of the dragons on Blodafeorde, the Bloody Peaks, remained consistently spoken, as it was both the most comfortably used by a dragon's tongue and remained the most potent in its resonance. The name of this language was lost with the eventual degradation and loss of the language itself, but is known now as Aummal Dragataeden, or Old Dragon's Tongue. The form of this language that was more fully preserved over the centuries since is known as Nymmal Dragataeden, or New Dragon's Tongue.

The fourth and final version of Life created by Patil was one made in a semblance of her own form; bipedal, with arms fit to reach high and hands fit to hold and shape. They were named Folmen, from the draconic word meaning "to hold", and later Heomen, meaning "to paint or write." Now they are known as human.

With this complete, Patil was drawn through the Sun into the Upper Realm of Light, called then Beoralriche, where she should remain until the end of the Age. However, her presence was not absent in the Transient Realm, as there existed on the Globe five fixed Lines to Beoralriche across its largest continent, where Light would pour forth continually to drive away any Darkness which would appear; three rested along the path of the Great Line, two in the forest and one on the shore of Gefarimme, one rested in the North on the plains, and one sat high in Blodafeorde, on the highest peaks to the South. It was through these Lines that Patil could continue to influence the Transient Realm from Beoralriche.

It is also around this time that the Birth of Rot occurs. In the Northernmost part of the continent, where the reeds from the Plains had reached the sea, the Soul of the Mire itself had made contact with a Being of Chaos, who granted its plants life through death. This was the first instance of Chaotic Magic, and showed that even the will of plants could sway the balance of Order on the Globe should a swamp embrace its entropic potential. For this reason, the Mink Marshes would continue to have a particularly strong affinity with Chaos.

Darkness Arrives

It was with the finalization of Patil's designs that Darkness had encroached upon the Realm. It came in forms from beast to bogle, always a perverse imitation of the forms given to Life and often reflective of the specific malice or neglect that did allow it into the Realm. The neglect or destruction of Nature would bring gnarled, lurking things akin to the animals which did live there, or the wholesale possession of those creatures should they allow its power to corrupt them. The greed of a king exploiting his subjects for wealth may bring from the woods a hungry beast which bleeds gold to lure victims, or contort that very king into a vampire. In this way, even Darkness works in accordance with the Law of Resonance.

These monsters, averse to Light, were greatly weakened by the presence of the Sun, and only the strongest of them could even attempt to encroach upon the lands close to the Lines to Beoralriche. However, they did prosper in those shadowy reaches, be they the shaded understory of the great Beoralheome Forest, or the dark depths of Sverdarimmen and Gefarimmen (the Seas to the East and West respectively), or the shadows cast by hillock and mountain alike from the Hillshades to Blodafeorde in the South. At night, when the light of the Sun is absent, even the plains to the North were not safe from their presence.

For a time, these forces of Darkness were quelled by the might of Dragons, who took it upon themselves to protect the animals and men of the continent. Unfortunately, the scope of their influence was limited by their population, which did not grow with that of the men and animals which they watched over. At this time, the humans had lived together around the Line to Beoralriche that lay at the center of Beoralheome, where Light poured out from a Great Tree as sap, so plentiful that it flowed outwards in great glowing streams. Around this tree they had founded a shrine to Patil, called Fidascelge (or, "the Shrine of the Tree"), and the Dragons had positioned themselves as protectors of this shrine, but as it grew they felt it more and more pertinent to teach humans in the ways of Speech and Breath, their two most potent and primal affinities.

The tongues of men were more flexible than those of Dragons, and more capable of diverse and powerful Speech. However, their Bodies were not made to hold Dragon's Breath, nor were they born with an Internalized Line to breathe from. To bridge the difference in capabilities required innovations twofold, one from a Dragon named Afabeofetal Aegafolmetin (or, "Strong Enough to Stop the River, Gentle Enough to Hold the Egg") and another from a human named Agataedil (or, "Bird's Tongue").

Afabeofetal Aegafolmetin's contribution was a method of exposure, in which they would hold a willing human in their mouth for three days, during which the Dragon would open their Internalized Line yet hold back their Breath, and the soul of the human would resonate with its presence and take a fragment of the Line to use as a catalytic seed of sorts for their own magic. This required a great deal of delicacy and resilience on the Dragon's part, and few were strong enough to safely take this role. Agataedil's contribution was a method of identifying and adapting to a Physical Essence so that the Body would accept and contain a Line to that Essence's Realm without rejection. She recommended meditating first for a day in a thunderstorm on the windswept beaches of Gefarimme, then in a sandstorm on the steaming mesas of the Hillshades, then finally for a day in the putrid mires of the Mink Marshes, meditating on which sensations fortified and resonated with the Body and, more importantly, which emotions felt in the soul resonated with the Essences that surrounded it in these storms. This would determine which Essence their Body would accept most readily, and in turn which Dragon should allow them to inherit their Breath.

From the humans who would attempt to learn these methods of attaining Dragon's Breath, this process required an extreme amount of dedication to learning these arts, but it also required a tremendous amount of trust in the Dragons involved. Unfortunately, in Fidascelge this trust was quickly wearing thin. The number of men had, at this time, expanded to near Fidascelge's fullest capacity, and many wanted to expand outward, leaving the shrine to establish their own separate settlements. The Dragons objected to this, as it would either spread their protective capabilities thin or leave those who decided to leave unprotected from the beasts that wandered beyond the shrine's walls. Eventually, the Dragons suggested prohibiting any and all attempts to leave the shrines by those who were not trained by them in Dragon's Breath.

Soon, humans began to voice the belief that the Dragons were tyrannical. After all, they kept humanity trapped within the Shrine, and only those few that proved their trust and devotion for the Dragons could leave or use their Breath. Many shunned the rule of the Dragons, taking a new Tongue that the Dragons could not even pronounce, with which they equated Dragons to monsters and protection to imprisonment. Some even began plotting the destruction of the Dragons and the theft of their power.

One human, who went by the name of Encws (though he was born with the name Anfaeltin), braved the meditations of Agataedil and seated himself in the mouth of the mentor dragon Blostabraedal Blostasaedin. Once the Dragon held its Breath back, Encws drew a spear from his shawl and threw it down Blostabraedal Blostasaedin's throat. The Dragon spat Encws out with such force that he broke many bones, and from that day could not walk again. For seventy years after, Blostabraedal Blostasaedin's sugar-breath was red and wet with the blood that poured from the great wound the spear left in their throat, and they were frequently ill.

It was after this incident that the Dragons made plans to depart from Fidascelge. They had no desire to fight back against a growing rebellion, and felt that those who chose to rebel no longer deserved their protection anyways. They took on their backs those who they had already granted Breath and those who remained loyal to them and flew South, not stopping until they had arrived in the highest peaks of Blodafeorde, where the humans that were left behind had no chance of arriving on foot. There, they found the Southernmost Line to Beoralheome, where they founded a new shrine to Patil, Dragascelge (or, "The Shrine of Dragons").

The following years were not easy on those left at Fidascelge. Those who attempted to leave the shrine rarely survived for long, as the paths were dark and treacherous and the woods were rife with beast and behemoth. Those who chose to stay encountered conflict within the shrine, as opposing ideologies attempted to fill the void left by the absence of the Dragons as a ruling power. As populations continued to grow, so too did the strength of these conflicts. At the peak of this conflict, there were no fewer than thirty seven individuals who had declared themselves the King of Fidascelge, each with some considerable number of followers. As these conflicts grew, so too did the desire for safe passage through the Beoralheome and, ideally, the discovery and founding of a new and distant shrine.

The Founding of Alchascelge

Of the Kings of Fidascelge, few had as large of a following as Swter (who would change his name to Suteorin when taking the title of King, his reasoning being that a name in the Dragon's tongue would fit one who took on the Dragon's position as ruler). Swter claimed that the Soul of the Beoralheome had called him to travel West, so that he would establish a Shrine there. From his followers he enlisted an envoy to guide him and his family towards where he was called, through the darkest reaches of the Beoralheome. They armed themselves with spears carved from the fallen branches of the Great Tree of Fidascelge, with points chiseled from its resin, and armored themselves in the thick leather of deer.

They had traveled for seven days, during which not a single beast or ghoul was encountered on the path, when they reached the bend of a river which flowed so strongly that they could not pass. When they made camp, they realized it was not by good fortune that they had not encountered any fearsome creatures on the way, for a mass of monsters had been waiting until the group was cornered at this bend to strike. They laid waste to the camp, killing Suteorin, his envoy, and his wife.

His daughter, Bledil, had hidden herself beneath her father's enormous cloak and was the last to be found by the beasts. However, before they could harm her they were set upon by the wolves of the forest, whose great claws and fangs made short work of the banshees and bogles. The wolves then turned to Bledil, and bid her come, so that they would lead her West, where her father was headed. Through the next thirty days, she walked with the wolves by day, and rode on the wolves by night. They hunted for her and scared away the monsters of the woods, and she would in time learn to speak their thoughts with her own words. They told her that soon they would arrive at a new shrine.

One wolf, which Bledil named Cawdle, had grown closest to her, as she would frequently ride his back as he hunted and clean his wounds after fights with the night beasts.

One night, Bledil separated from the group, hoping to find a river or lake in which she could wash her hands and feet, as the wolves did not ever bathe. She found a glade where a herd of elk grazed, and they asked how she had traveled so far from home and she told them that the wolves had guided her here. The elks apologized, and told her that she should not trust the wolves, that they had made a plan to take a king and turn him into a wolf, so that he may bring them within the walls of Alchascelge and they may take the role the Dragons once held. When she told them that her father was a king, and that he had mistaken the call of the wolves for that of the Beoralheome itself, they told her that the wolves were not leading her to a new shrine. They told her that the elks knew of a Line to Beoralriche in these woods, and could leave her there if she left the wolves.

However, Bledil was indebted to the wolves, as they had saved her life, and she returned to them by morning. The wolves knew that she had changed, for as she could voice their thoughts they could feel hers, and they knew that the elk had revealed their plans. They set upon Bledil and she ran, and they would have been quickly upon her had Cawdle not taken her upon his back and ran with her to the glade where the elk still waited.

The elk, knowing what had happened, led the two through the Western Beoralheome until they came to a valley between two hills, where the wild grapes grew plentifully and Light poured from a wellspring in the clearing. They offered to keep Bledil safe here, but she knew she had to return to Fidascelge.

She pulled back the ears of Cawdle, and his body worked to reflect her will and he became the first hound, led by man to be greater than wolf. Bledil rode him, then, back to Fidascelge, and she told them of the wolves and elk and the valley. She and Cawdle led many back across the forest to the wellspring, taking the paths of the elks which now were shown to her. There, they established a new shrine to Patil and the Elks, which they had named Alchascelge, and they had made Bledil its Queen. She would accept the crown, and name herself Vardafange, the Wolfsbane.

The Founding of Eftascelge

While there were many Kings in Fidascelge, there were far, far more commoners. Those who left the walls were often pilgrims or crusaders, looking to travel far into the continent, but occasionally those beyond the walls were fishermen, pushed to travel beyond the walls of Fidascelge when the waters within became unpopulated. It was for this reason that a band of thirty fishermen, men and women, young and old, had traveled into the Eastern Beoralheome, leaving as the sun rose and hoping to return before it set, lest the night creatures come upon them. When they had found a teeming river, they set out their nets and rods and spears and fished until their baskets were full, and headed back the way they came.

However, the path from which they came was winding and shifted with the land, and they became lost as the sun had set. From the dark, the great cackling and growling of the night creatures grew loud and close, and the band feared for their life. Then, a great thunderstorm erupted, and as the night creatures set upon the fishermen they were blown and washed away by its great torrents and winds, and struck by its great bolts. The fishermen, by good fortune, had stood at the eye of the storm, and were unharmed by its strength.

For thirty days, as the eye moved the fishermen traveled with it, as it kept the beasts at bay and guided them through the woods. The storm headed East, and as it passed rivers and lakes, the storm would wash fish upon the shore, and the fishermen would keep their baskets full. After the thirtieth day, though, the storm had ceased to guide the band to waters, and drifted North. The fishermen looked out through the storm, and several spied a great beam of light in the East that shined both day and night, and they believed it to be a Line for a new shrine, and that the storm had guided them to it. However, the storm did not drift towards the Light, and instead continued North. Twelve of the thirty fishermen, starving and desperate, had left the eye of the storm during this time, hoping to reach that Line before it grew too distant. None of those who left the eye survived, either killed by the storm or the night creatures which found them quickly after the storm had passed.

Those who stayed with the storm, through their hunger and weariness, were taken North, then East, then South, and they found that the storm had once again approached the Light they had seen in the distance. On the Eastern edge of the continent, facing out over the Gefarimme, was a cliff which hung over the sea, and on this cliff there was a grotto, in which many lizards slept, from which Light flowed like water in streams which poured out into the sea in great waterfalls. It was apparent to those fishermen who had arrived here, when the storm hung over the Line to Beoralheome and dissipated, that those who went East when the Light was visible before would only have been led to the foot of the steep cliffs which faced Gefarimme, and that only by the path the storm had taken could they have arrived at the source of the Light.

The fishermen then established a shrine to Patil there, and found the fish were plentiful on the shore below, and found that great masses of lizards would warm themselves upon the rocks. They would return to Fidascelge, and lead the other fishermen and commoners there to their new shrine in the East, which would be named Eftascelge, the Shrine of Lizards.

The Founding of Massascelge

There were, in Fidascelge, a number of terrible Kings who, seeing overpopulation as the greatest threat the shrine could face, asked the shepherds and the craftsmen and the fieldworkers and the artisans to cast themselves out beyond the walls, so that those citizens they found integral to the well-being of the town, the merchants and the nobles, whose wealth indicated their worth, would not be snuffed out as the land's resources were stretched thin. There were four Kings still within Fidascelge who disagreed, and when the other Kings commanded the villeins to leave and the shepherds did not know what else to do but go, these four Kings walked with them through the Beoralheome.

When the first night had fallen, the four Kings and the villeins were set upon by kobold and kelpie, and many were killed before the sun had risen again. To lift the spirit of those who survived, as many were injured and all were dejected, the youngest of the four Kings, called Merrymowthe, had procured a flute and played a tune; their pains faded away with the sound of the song, and from the woods a swarm of squirrels and weasels and field mice and rodents and mustelids did gather, enthralled by the playing. The rodents did lead the masses to the North, where they had made their homes in the verdant fields that were spread out beyond the Beoralheome.

They had found, in the center of these plains, a pasture where the grass glowed, so full of the Light which seeped out from the ground which came from the Beoralheome, and they were quick to establish a shrine to Patil here, and surrounded it with all manner of farmland. However, they soon found that many of their crops would not last even a single season, and many of the fowl which they raised were hunted in the night, and many were left hungry. They learned soon that the very rodents which led them here had feasted on what they had grown and left none for them.

The Kings, at once, did each play their flutes in harmony, and in their chords did they separate the rats from the stoats from the mice and from the hares, and across the fields did call them and guide them, and those who felt the thrall and rejoiced remained, while those who feared the control of man fled North to the marshes, from then on named the Mink Marshes for this reason, as the stoats and rats did swarm there en masse. From this, the humans had secured their crops and had, from this day onward, named their shrine Massascelge, or the Shrine of Mice.

The Years to Follow

In the years that would come after the founding of the Shrines, the bodies of humanity would work to reflect the Globe, and many would change drastically in the process, taking on forms which best suited their new homes. In the West, those in and around Alchascelge would grow to resemble the animals which grazed on the grapes and grass and ran through the woods, taking horns and hooves and other features of the ram and elk and similar beasts, and taking the name Woodborn for their lineage. In the East, on the shores, they took the traits of lizards and fish, growing scales across their skin, gills along their necks, and webs between their fingers, and the term Shorefolk was coined among them for their ilk. In the North, their teeth grew flat, their hair grew soft, and their fingers grew prints, to better feel textures like the delicate hands of the rodents of the field, and living in the plains they took to referring to those of their kind as Plainpeople. In the South, at Dragascelge, they took the wings and claws of the birds which nested in those peaks, and they took the name Drakeblood for their kind. None remained in Fidascelge, for after the remaining Kings were abandoned by those they had pushed out they found that they had no real means of surviving there alone.

And it would come to pass that civilizations would grow to surround the four shrines at the corners of the continent. Each shrine served as both the last point of respite from the darkness and as a place of worship, for the most fervent prayers made at a shrine were often answered by the greater actions of Patil, who sat enthroned in the Beoralriche and focused all of her attention on maintaining balance in the Transient Realm. She would sway the weather to favor those who prayed for their harvest and hearth, she would bring good fortune to those observing holy days and festivals, and she would grant all manner of blessings to those who had seeked her favor to fight the beasts of the night and protect the living.

However, Patil refused to intervene in any conflict between one man and another where the forces of darkness were not at play. This was especially true in the case of wars, which unfortunately would crop up from time to time as the nascent civilisations grew and their conflicts grew with them. She swore that her power was for protecting life against the dark, and thus getting involved in conflicts among the living would only distract from that goal. Additionally, she could not hope to both maintain the adoration and worship of all groups and nations while favoring or advocating for one over any other. In this regard, she remained wholly impartial in any such affairs. In theory, this would have worked to dissuade a good number of conflicts over the years; within any given conflict, an acknowledgement of Patil's impartiality therein could serve as a reminder of both sides' shared objectives under her guidance and, in turn, the relative insignificance of all other conflict. If she were to intervene, it would be in an instance where the side at fault was provably participating in the willful destruction of life and obstruction of agency. Aside from the most dramatic of conflicts, this was rarely the case in interpersonal affairs. It was under this guidance that these civilizations developed after their founding.

At Eftascelge, they cut many stones from the rocky cliffs that lined the shores and from them erected a stronghold around their grotto on the cliffside. Around the stronghold grew a city which overlooked the sea, and along the shore a great number of smaller towns did form to house the fishermen who fed the city. As the backbone of the city, those fishermen were promised unconditional solace in the stronghold should trouble beset the shores. Aside from the Drakebloods, the Shorefolk would expand the furthest South along the Eastern shore continent, and they would spread along the Northern shores almost enough to reach the Mink Marshes. However, to avoid conflict with the Woodborn or the Plainpeople, they ceded most of their right to expand Westward, save some moderate portion of the Eastern Beoralheome Forest. This they accepted, as they were most aptly suited for life on the sea. In time, they would become known for their impressive sea vessels, their tenacity in the face of storm and hardship, and their collectivism.

At Alchascelge, they felled a large number of trees which lined the valley and with their timber erected two towering houses. The first was for Vardafange and her progeny, chosen by fate to lead her people. The second was for the church, led by a number of scholars devoted to the interpretation of Patil's will and the study of the Globe. As a great city grew to fill the valley, the two codified their structures of the two houses, so as to solidify the foundation of the new governance; hierarchies were established within each, and balances of influence were established between each. Their vineyards grew plentiful, and the woods were full of game. Thus, despite the ever-present shade of the forest, House Vardefange expanded the reach of their influence deep into the Beoralheome. They would erect the first outpost for what would later become the Goodhunters of the Woods, a band of seasoned hunters dedicated to keeping the territory of the queendom safe from the beasts which lurked in the darker recesses of the woods.

At Massascelge, the farmlands spread to wherever the sun shone on the verdant fields, and there the wheat was plentiful. In their comfort, their city was the least centralized, as the open fields left little space for the night creatures to hide from the light of the sun and so they were least drawn to the defense from them which their light-laden meadow would provide. The shrine proper at Massascelge instead became a center for artists and philosophers, given the luxury of creative endeavors in the absence of hardship. They were led by their four kings, who took the House names of Stotafangen, Rattafangen, Cannafangen, and Acannafangen in the same manner as Alchascelge's rulers. Rather than determining their successors via offspring like the line of Vardafange, they acted much the same as the local master artisans, choosing apprentices on merits of social aptitude and charismatic prowess and allowing the best among them to replace them upon retirement.

Life in the plains was not entirely without comeuppance, though. Some number of years into the city's development, the daughter of a farmer who had founded a homestead in the plains' Northernmost reaches had wandered deep into the Mink Marshes. There, she had gone missing for some number of months, and when she returned her family felt that she had been touched by some concerning force found deep within the Marshes. Her attitude had changed considerably, and she exhibited unnatural capabilities that surpassed even the Drakebloods, her family professing that she had exhibited the ability to tell the future, and she spoke in a tongue that sounded older than the dragons'. A farmer tending to a neighboring stretch of land heard a great fight occurring on this family's land and saw the father and the daughter in a heated argument. Having heard of her disturbing change in demeanor and fearing what might happen to the father, the neighboring farmer shot at her with his longbow. The father and the neighboring farmer both later detailed witnessing the amount of blood which poured from the wound in her chest being far greater than what should have been possible. In two weeks time, a great plague erupted in the plains, affecting first those closest to where the shooting of the farmer's daughter had occurred and then spreading to those in the city, where even the strongest prayers to Patil did little to slow its progression and an estimated half of all Plainpeople had died before the plague had passed. From then on, the Plainpeople knew to avoid the Mink Marshes.

At Dragascelge, the Dragons had established their shrine in a deep cavern on a high peak in Blodafeorde, where crystals had formed in its deepest recesses which shone bright with the light of the Beoralheome. The Drakebloods, descended from the humans who had proven themselves loyal to the Dragons and accompanied them in their migration to Blodafeorde, worked to carve their own tenements into the faces of the Bloody Peaks and felled timber to fortify their structures. At these higher altitudes, Drakebloods depended on game hunting for much of their food, as well as the cultivation of root vegetables and mushrooms. Though the Drakebloods depended on the protection of the Dragons through much of the early years of their introduction to Blodafeorde, neither group saw their society as hierarchical. While the Dragons had taught the Drakebloods magic, the Dragons truly believed that they would one day be surpassed in skill, as Humans exhibited much more capable and resonant applications of speech and will. After all, several generations in the mountains were enough for the Drakebloods to grow wings, so resonant were their bodies with the Globe. Additionally, both had to earn their entry to the shrine proper, Dragons needed to earn acceptance into their Shrine Council and Drakebloods needing to make a pilgrimage to the Beoralheome, demonstrating their agency in their ability to make the journey that once necessitated the help of the Dragons.

None would settle in the Hillshades at this time, which stretched from the Southernmost border of the Beoralheome to the Northernmost cliffs of Blodafeorde. The mesas' dark and arid reaches were uncommonly rife with beasts and inhospitable to travelers. To create any sort of permanent residence there would have been nigh impossible, and there was little reason to travel that far South once the shrines within and North of the Beoralheome were fully established. Only the Dragons seemed capable of passing over these lands without any difficulty, and still they preferred to remain cloistered at Dragascelge.

The Centuries' War

The origins of the Centuries' War are contested by many, so long was the fighting and so numerous the retellings by different nations and sides. Little was recorded of the inciting incidents as they occurred, yet much was told of them by those using their impassioned tales to rally their troops, events warped and reworded by the war itself. What is indisputably known, mostly from what was recorded in the few years before the start of the war, is that a famine had struck the Shorefolk.

Though the Shorefolk were most well known for their fishing, much of their diet depended on the salt-tolerant plants that they could cultivate plentifully on the coast; mostly seaweeds, roots, and the occasional hardy grain. It did not allow for a notably varied diet, but these few crops sustained the nation and were beloved by the Shorefolk. They had learned to make the most of every ingredient they had available. While this earned them an unsavory culinary reputation by the Woodborn and the Plainpeople, it was enough for them to survive and thrive for centuries. This would unfortunately not be the case forever. For whatever reason, be it over-intense cultivation, the lack of proper crop rotation, a pestilence or rot in the dirt itself, or even some malignant curse not repelled by the prayers of the nation's farmers to Patil, there eventually came a season where many of the Shorefolk's crops had refused to grow.

This was not immediately catastrophic, as they had the foresight to keep a decent amount of their crops dried and stored in case of a poor harvest. It was only once they had stretched the last of what they had stored to its fullest extent that the Kings of Massascelge had arrived at Eftascelge with a proposition. They offered to sell a portion of the Massascelge's excess harvest to the Shorefolk for a price of metals, spirits, and fabrics. While it was admittedly exorbitant, the price was agreed upon by those at the Stronghold of Eftascelge. When it was delivered, those at the shrine worked then to distribute food to those living on the shores. They had expected this to have been enough to be enough to feed them until the next harvest. Unfortunately, as it had the year before, the harvest disappointed again, producing very little. The famine was not nearly as temporary of an issue as anyone had expected and hoped for it to be. Those in charge of trade at the Stronghold of Eftascelge were forced to make a tough decision, knowing they could not continue to pay the price to feed all of the Shorefolk that the Plainpeople had asked for. They decided to instead pay only to feed those at the City of Eftascelge itself, and have those beyond its walls fend for themselves with what meager forages they could muster, believing that their highest priority was ensuring the continued good health and functioning of the shrine proper.

It was not long after this that many of those living along the Gefarimme began to move across the Shorefolk nation's Western border, into the Beoralheome. This became known as the Great Trespass, where many of the Shorefolk beyond Eftascelge traveled into land that they had previously ceded to the Woodborn of Alchascelge. It started with small trespasses, with foragers coming in groups to gather the roots and herbs that grew deeper in the woods. Then, communities would start to travel into the woods en masse, when the last of their resources on the shore ran out. In the borders of these woods, they began establishing small settlements of their own. To this, the governing body of Eftascelge turned a blind eye, not wanting to chastise those it had failed to provide for and not wanting to get in the way of what could have been a perfectly good solution to their famine problems.

There were a number of small Woodborn towns in the Easternmost reaches of the Beoralheome. While these communities had their right to settle in those woods protected by the Royal Authority of Alchascelge, they were not by any means the most well off residents of the Forest. Often, they were lower class Woodborn who, without a position in nobility or clergy, had hoped to make a better life beyond the Valley of Massascelge than they had any chance of having in the shrine proper. These were hunters and foragers, homesteaders hoping to attain security and safety. As the Shorefolk moved West, they would eventually encroach upon the land owned by these Woodborn.

From there, things would escalate. The Woodborn would fend for their land, believing themselves to have the moral and legal right to it, and the Shorefolk would fight back, believing themselves to need the land more and knowing their own government would not hold them accountable for anything they did. Land disputes would become brawls, then brawls would become battles, both nations rallying forces from their respective capitals to reinforce their efforts to expand and protect their claims. Though Eftascelge would eventually reach an end to its famine, it no longer had a place for those who had moved West, as those communities who had remained on the shores through the troubled harvests had grown and restored the land the others had left behind in their absence, essentially taking their place. This was not dissimilar to how Alchascelge no longer had a place for those Woodborn who had moved East, and they similarly could not simply evacuate the disputed land.

The longer both sides spent erecting, fortifying, and defending settlements in this growing stretch of the Beoralheome, the greater the stakes became for those who could not return from where they had claimed land. In turn, they would garner more approval from their respective nations' capitals. Both continued to supply their contested fronts, knowing that the options were to prolong a war of attrition or complete the near impossible task of bringing the battle all the way to the other shrine. It would evolve from a territory dispute to an ideological one, as both sides would take to attributing the other's tenacity to corrupt ideals and a warmongering nature. Many in Alchascelge perceived the Shorefolk as primitive seaweed-eaters with no sense of honor or hierarchy, whose Great Trespass was caused by a total lack of respect for the Laws of Men or the Order of the Globe, which needed to be forcefully evicted from their land in accordance with the Laws of their Kings. A great many in Eftascelge, in turn, viewed the Woodborn nation as one of ruthless zealots under the rule of a tyrant with a heretical claim to the throne, who claimed to possess the poise of elks yet acted with the brutality of hounds. In a sense, this was the period where national identities solidified, where only at the point of contrast did the two nations develop passionate defenses of their lifestyles, histories, and governance.

As with all prior conflicts between men, Patil did little to interfere. It was by her blessing that good harvest had returned to the Shorefolk eventually; perhaps she had hoped that that alone would draw the war to an end, but it was beyond her means to settle the matter directly. For many, their faith in her guidance wavered in this conflict, as pacifism did little to make amends.

As the fight between the nations grew, Massascelge remained largely uninvolved throughout much of the early war. Its trade of provisions with Eftascelge would eventually reach an end as the Shorefolk became less desperate for their support, though they hardly relied on that avenue of trade for much more than luxury. Eventually, though, they did discover another lucrative trade opportunity that the war had introduced: selling arms. As they had a number of skilled smiths, sufficient resources, and a relative lack of conflicts to attend to, they had everything they needed to produce a large number of high quality weapons, produced by artisans trained by a long line of masters, which could be traded for at a premium. Moreover, they realized that, if they did so covertly, they could initiate trade with both sides of the war, selling swords to Alchascelge in exchange for fine wine and furs and selling spears to Eftascelge in exchange for salt and linen. To each army, they sold the idea that greater arms would bring a swifter end to the war, while in turn bolstering the other side, knowing a longer war meant the purchase of yet more arms.

This would eventually backfire for Massascelge, as soldiers eventually noted the similar craftsmanship of their own weapons and those of their enemies and grew wise to their ploy. The armies of both sides would call for boycotts of the use of these arms, and the use and purchase of such weapons became greatly stigmatized. There were even a number of calls to bring the war to Massascelge, and while an official war against the Plainpeople was never recognized by either nations' government, slowly the war would spread North into the Sunlit Plains regardless. Few direct attacks were led against Massascelge itself by either the Shorefolk or the Woodborn, as any concentrated effort on a Northward campaign would spread their forces too thin and give the other side an opportunity to take advantage of their division. Still, there were frequent attacks on Plainpeople settlements in the Southern half of the plains, and fights between the Shorefolk and Woodborn would frequently use the open plains as a battlefield, as it was more suitable than the forest. Despite their relative prosperity, the defenses of the Plainpeople were especially ineffective against the tactics of those who had trained to fight in far worse conditions than the open fields. If they hadn't already been producing an excess of arms for trade and had the benefit of only entering the fray after both other sides had already been fighting for a number of years, they likely would have been the worst faring nation in the war.

Through these inciting conflicts, the Centuries' War formed. The war seemed infinitely self-perpetuating, the battlefields ever expanding and the borders of contested lands ever shifting. Coordinated attacks and defenses of various scales by various nations seemed to always creep closer to the Capital Shrines, the towns in their wakes left in various states of destruction, repair, founding, refounding, siege, reprieve, and turmoil.

A New Magic

There was, in the Shorefolk town of Summerled, a girl by the name of Dene. Her mother, a Shorefolk and the daughter of the town's late founder, had some passing affair with a Woodborn she had met while traveling the Beoralheome. As a result, Dene was born with both horns and scales, which drew the ire of many in Summerled. She was an odd child, with a habit of staring at the sky at night and asking too many strange questions to those she met. Her mother would do her best to raise her well and protect her from the scorn and abuse of the others in town, and she and her daughter were afforded some level of clemency from those who had respected her father. Unfortunately, when Summerled was assailed by a band of Woodborn combatants, Dene's mother was killed in the onslaught. The clemency she was granted was not similarly afforded to her daughter, and they were quick to drive Dene out, believing wholly that she had brought bad luck to Summerled.

On her own and with nowhere else to go, Dene would travel North of the Beoralheome. She knew she would not be accepted by either the Shorefolk or the Woodborn beyond her own town, but felt she had a chance in Massascelge. She had found a small town in the Northern stretches of the Sunlit Plains, called Gridshire, who had not yet grown cold towards travelers, as by then the war had yet to reach them. Initially, they were willing to take her in as a refugee, and even showed some considerable amount of sympathy towards her plight. Unfortunately, though, they had found her demeanor off-putting; she had not lost any of the strangeness she had possessed as a child, and spoke in a way that reminded the Plainpeople too much of those who had traveled to the Mink Marshes and came back changed. In time, Gridshire, like Summerled, would reject her for this, and she would continue North to the Mink Marshes.

The Mink Marshes were a dour place, wholly unwelcoming to travelers, the air foul and the earth sodden. For weeks, Dene wandered its overgrown quagmires, feet blistered and skin muddy. The air felt constantly full with some unnerving tension, as though brimming with some strange energy. There was no water fresh enough to drink, and she fed only on cattails and chicory, having not the tools or skills necessary to hunt the stoats and snakes which hid among the grass. The sun was hot and wholly unshaded by day, and at night the ground was cold and damp. The path gnawed at her, and she grew weaker every day. One night, she collapsed from weariness on some lone grassy knoll, believing that she would die then, starved and filthy.

And yet, in all of this, she did not despise the Marshes. She did not fault it for its inhospitality, nor did she blame it for failing to feed her well. She did not sorrow in her filthiness or her hunger, and found that in her weeks traveling here she had barely thought of them at all. She did not fear for her death here, nor did she lament, because in the full embrace of the climate she had felt more at home now than she had in any town. The air's strange energy, which pervaded still, seemed to pull close to her where she laid, and she welcomed it.

She felt as though her soul had risen out of her body like a vapor to mingle with the energies around her, pulled at by the air and pulling back in turn, like two attracted forces. She felt, within her soul, the breeze inside which blew her to the North. Then, as if in turn, she felt the wind around her begin to blow as well. She focused then her stream of thought, which often trickled and flowed around in little rivulets, and drowned out the world around her. In turn, the sky around her grew thick, and it began to rain where she had lain, washing the dirt from her body. She thought then of the fire in her mind, which flickered more brightly when she could stare into the open sky, and at once the rain ceased. Flames erupted from the air around her, and the earth on which she had lain grew dry and warm. In her epiphany, she sat up, no longer content to die. The Globe had worked to bring her comfort, and she knew that she could spread it to others now. She had felt a magic in the air itself, one which man had no chance to contact since those days when they had felt it in the Dragons' maws.

Dene would spend a number of years studying and perfecting her new magical practice in the Mink Marshes, learning how her magic worked and how she could teach the gift to others. She would often cross paths with others in the Marshes, often those who had fled there to escape the conflicts down South, sometimes those who had felt the Marshes call to them and came there of their own volition. Most were glad to accept her assistance on the road but feared her conjuring tricks. Still, a small number, mostly of those who had felt called by the Marshes, studied under her in hopes to connect with their own magical potential. Occasionally, she would find someone who had traveled far deeper into the Marshes than herself, and they would have the strangest manner and sometimes even stranger magical gifts. More often than not, the nature of their magics would elude her, but they often pointed to the potential of her own craft.

She taught no more than nine in the ways of this newfound magic, for many feared it and others lacked the necessary aptitude to practice it themselves. Of the nine she had taught, the practices they had developed to connect with the Globe's latent magical potential often varied superficially from her own, but the resulting magics varied drastically in effect. Unlike the magic taught by Dragons, where a Line to an Essential Realm was internalized and its contents were released from within, the magic practiced here worked by baring one's soul to the ambient Lines which surrounded the Globe unseen. Should any of those Lines resonate with the aspects of the soul, they would briefly manifest the essence held within.

One of her students, a Plainperson by the name of Lwter, could sing in a way that elicited emotions far more potent than any natural song, pulling energy straight from the Emotional Essential Realms and imbuing his songs with them. Another, a Woodborn by the name of Rosin, could set an empty cask on the ground and, by merely focusing her intentions upon it, could cause it to fill to the brim with wine. Moraunt, a Shorefolk, had learned to bring rain from the sky with his sorrow and lightning with his rage, and could just as easily clear the skies with his joy. When a student could fully grasp their magical potential, they would leave Dene and return South, swearing that they would spread what they learned to their people.

Her final student was a Drakeblood by the name of Fugil. He had journeyed from Dragascelge to the Beoralheome in an attempted pilgrimage to Fidascelge, which lay abandoned somewhere in those woods. Fugil had hoped to become a priest, making his pilgrimage to earn access into the shrine proper at Dragascelge. However, becoming caught up in the conflicts within the forest, he had found himself traveling far further North than he had originally intended. Eventually, he would reach the Marshes and meet Dene. Though he could not replicate Dene's magical practices, his knowledge of Dragon's Breath, in conjunction with Dene's knowledge of her own practices, provided insight into the broader workings of magic as they occurred across the Transient Realm. While the purpose of the pilgrimage to Fidascelge was, in part, to remind the Drakebloods of what they had gained through their migration to Blodafeorde (and Fugil had initially fully intended to witness that in his travels), his time with Dene had instead illuminated a certain potential present in those that lived North of the Hillshades that he was unsure could be rekindled in Dragascelge. He would stay with her for many years before returning South to Dragascelge.

Dene was not the first to independently discover a novel magical practice (and even among her students she wasn't the last), but she was the first to make a concerted effort to spread what she had learned to others, who in turn worked to teach their respective peoples in the ways of magic. It was during this time that she earned the title of Myrskaliche, or the Witch of the Marsh, by those who learned of her from her students.

Unfortunately, the effects of this exchange of information were not what Dene had hoped for. While she envisioned magic as a way to ease the suffering of humanity, it was instead adopted by many as a weapon, more powerful than any that had been created by human hands before. Some soldiers would learn to turn their rage into storms of fire upon their foes, others would curse their blades to leave acidic wounds that never stopped bleeding. Others still would learn songs that could supernaturally inspire their men to fight through any pain, or rituals to turn the earth beneath the feet of enemies into viscous tar. Though some found ways to use magic as a tool to heal or ease the suffering of those affected by the war, the vast majority of those in these warring nations would see magic as an extremely effective weapon to be used against their enemies.

When Dene had returned South, some number of years after Fugil had departed, she had hoped to find a better world than the one she had fled from. Instead, upon arriving again in Gridshire, she found that the continent was still in the very same war as it had been when she had left, now prolonged by the very powers that she had discovered. In her rage and sorrow, she charged through Massascelge, a great storm of hail and flames about her as she went, until she had arrived at the shrine proper. The guards of Massascelge were powerless to keep her from their glowing pasture, as her preternatural fervor had made her unstoppable.

Upon entering, she cried out to Patil, demanding that she do something about the war. Patil came before her, her visage appearing in the wind over the pasture, and she responded, saying that she had done all she could. She had brought an end to the famine the Shorefolk had faced, and she had kept harvests plentiful and the beasts of the night at bay. Dene, enraged by the emptiness of the Goddess's response, spat curses at Patil until her visage vanished. She stormed out from Massascelge and traveled North again, vowing not to return from the Marshes again until she had found a power there greater than a God.

The Myrskaliche was never seen again.

The Founding of Sirin's Firth

There was, along the Northern coast of Gefarimme, a lone harbor accessible only through careful navigation of a turbulent and rocky strait amid the cliffs. It was one of the strongest strategic footholds the Shorefolk held in the North, as it could receive reinforcements by sea far faster than the armies of Massascelge or Alchascelge could send them by land, and its position at the only point of the Northern coast suitable as a harbor allowed them to maintain near total control of the sea well into the war. Initially, though, it was founded as a market town for the trade of wheat (and later arms) with the Plainpeople. At this time, it was little more than a set of storehouses, docks, and a lighthouse, erected to help direct sailors through the perilous waters and jagged cliffs. Trade with the Plainpeople there would eventually cease when Massascelge was pulled into the war, but many Shorefolk continued to live there, cultivating the land and guarding the harbor.

Among those keeping the harbor, there was a fisher by the name of Sirin. She had learned some form of song-magics from her father (a captain by the name of Rowdale who once attempted to sail around the entire continent and attack Alchascelge from the West, only to end his expedition at the Northernmost reaches of the continent before returning home, only surviving by discovering his own magical potential on the way), and she was a mage of some renown. Her voice could soothe the tides as well as it could soothe the soul, so pleasant and resonant were her melodies.

One day, as Sirin worked to bring in her nets, there came news that a great army of Plainpeople came from the West, amassed to take the harbor for their own use. At once, a ship was sent to travel to the Stronghold of Eftascelge to request and transport military reinforcements. Those who remained at the harbor knew they would have to defend it until their reinforcements arrived. Sirin was tasked with keeping the lighthouse well lit, as it was likely that the requested aid would arrive by night, and without a light they likely could not enter the harbor.

The general of the approaching Plainperson army knew the harbor well, as he was once a merchant who traded frequently there. He knew that, to ensure a successful capture of the harbor, their attention should be focused on taking out the lighthouse and preventing the arrival of reinforcements by sea. Those at the harbor were prepared for a fight, but they weren't prepared for an attack so focused on a singular point. When night fell, the vanguard rushed the lighthouse before anyone could think to stop them.

Sirin, seeing the onslaught approach from atop the lighthouse's tower, brandished her father's cutlass and began to hum a melody of battle. Those outside the tower witnessed the flames in the lighthouse's lantern flare, until they grew almost blinding. The wind picked up from the sea, and a song amid screams rang clear from the tower until the reinforcements from Eftascelge docked. The Plainpeople were quickly driven from the harbor, as the Shorefolk were invigorated by Sirin's song. By the time the sun had risen, the battle was won and the Shorefolk were lauding Sirin as a hero. From that night on, the harbor was called Sirin's Firth in her honor.

The Fall of Sirin's Firth

As the war went on, and its potential as a military asset was more fully realized, Sirin's Firth would grow until it nearly matched the City of Eftascelge in size. Its borders were fortified, its farmlands were expanded, and its lighthouse was frequently restored. Its position allowed the Shorefolk to continually defend against any major offenses from Massascelge while allowing the Stronghold of Eftascelge to focus its own resources on the war with the Woodborn about the Beoralheome. Unfortunately, this period of wealth and success would not last.

Some number of decades after their initial navigation of a similar distance, the generals of Sirin's Firth had boarded their ships and traveled North again. Unlike their last voyage, the goal of this journey was not to circumnavigate the continent but instead to arrive again at that Northernmost tip of the continent, where it was rumored that Rowdale had stored away some great treasure he had stolen from the Plainpeople on his journey. Though many in Sirin's Firth decried this as a myth, there came by bird a message that put their cynicism to rest: the crew reported that they had found what they had sought, that it was better than any treasure they expected it to be, and that they were set to begin their return voyage with no issues. In celebration, a festival was prepared at the harbor. The kegs of their oldest spirits were brought out, bards were sailed in from the South, some traveled to the shrine to pray to Patil for her blessing, and feasts were made to prepare for the ship's arrival.

Unbeknownst to those at the harbor, the message they received had previously been intercepted by a Woodborn scout, who had relayed the information he had gleaned to the Woodborn forces situated Southwest of the Firth. It was by chance that among those situated so close to the harbor was Drosin of House Vardefange, second in line to the throne of Alchascelge, who had taken the position of general with hopes of proving himself more worthy of the throne than his elder brother. In a sense, he felt that the intercepted message was fate turning to his favor. He knew that this was an opportunity to catch the enemy unawares, as everyone at the harbor would likely be drunk and thoroughly unarmed. Additionally, he hoped to seize whatever it was that Rowdale had stolen from the Plainpeople. On his authority, a great army was amassed and prepared to arrive at Sirin's Firth on the day of the upcoming festival.

At noon, the voyagers returned to Sirin's Firth. An hour later, they had unloaded their ships. An hour after that, festivities began in full, with drinking and merriment in full swing. An hour after that, some commotion occurred at the storehouse where they had unloaded Rowdale's treasure, and many went to investigate. An hour after that, Drosin's men charged the harbor, the festival defenseless against their onslaught yet unnaturally distracted by something deeper within the Firth. An hour after that, a number of large shadows passed overhead, and the great call of a dragon was heard by all within the Firth. Then, the sky erupted in flames and ice and acid.